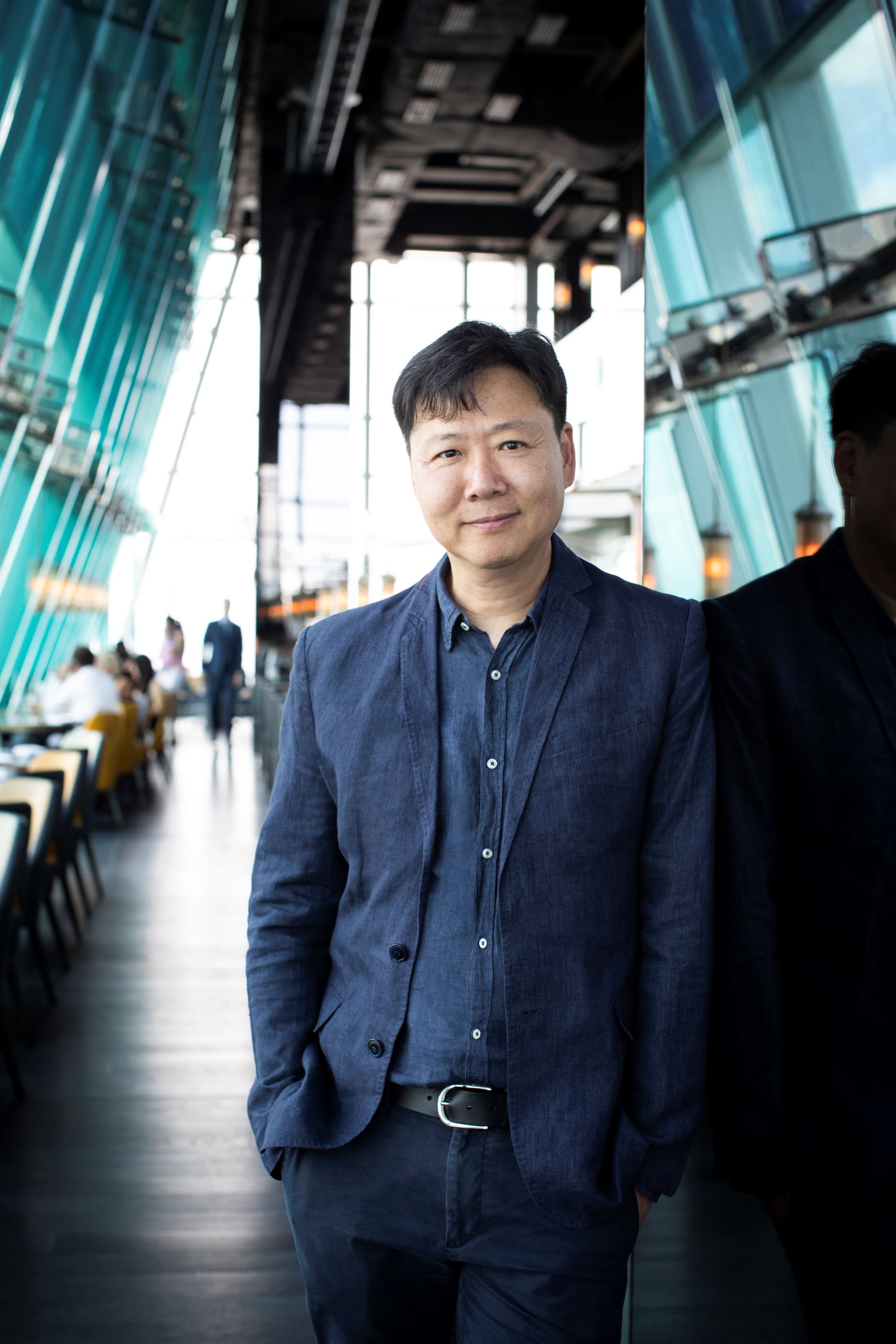

An interview with…

David Yeo

Restaurateur David Yeo, founder of the Aqua Restaurant Group in 2000, now runs over twenty prime site restaurants in major cities across the world.

Showing no signs of slowing down, David talks about the growth of his business empire and his plans for the future.

Hutong London, The Shard

GS What sparked your interest in running a restaurant?

DY I’ve always been a foodie, even when I was a partner in a major law firm in the 1990s. I was running project finance and going all over the place, but mainly in London and Hong Kong. I was one of those sad people you see with a trolly bag and a laptop going from hotel to hotel.

But I did get to eat out a lot, entertaining clients and so on, and I just felt that the food I was being served was unspectacular. It was all about ticking boxes. No one was really cooking with their heart, especially in the hotels. There was a lack of passion in the cooking, and it showed.

GS But in London at that time there was a restaurant revolution, with the likes of Nico Ladenis and Marco Pierre White making the headlines.

DY Yes, but they were the exceptions, and they were quite pricey. I’m talking about a mid-price point that would be accessible for most. You had the pubs and the pricey restaurants, but nothing really decent in the middle. There was a gap in the market. And I felt I could do something here in the UK, even though I actually opened my first restaurant in Hong Kong. That was in the year 2000.

GS Was it on a grand scale?

DY Oh no! It was a small restaurant, above a little market, in an area where not that many people would visit. It was little more than a boys’ canteen: a place for the lads to go to. And I adopted a rather a snotty attitude then. It was “We’ll cook how we want, and if you like it, stay. If you don’t like it, then go.”

Aqua Shard (above), Aqua New York (below left), Hutong Hong Kong (below right)

Aqua Kyoto, London

GS Were you cooking then?

DY No. I was still working as a Lawyer. But I persuaded a very good friend, Jocelyn Cunningham, to come in as GM. And Jocelyn got Greg Bunt, who was working in a hotel at the time, to come in as our chef. He’s now Culinary Director for The Four Seasons in the Middle East. The premise was simple; we’d have a small menu, but for each set of ingredients we’d cook two dishes; the first would be following a traditional recipe, and the second, using exactly the same ingredients, would be something totally new. So at least half the menu were new creations! And the concept worked. Within nine months we were voted by Conde Nast as one of the “Hottest new tables in the World”. And within four years, with Aqua, we had a Michelin Star.

GS Did you have a plan, to be recognised on the world stage?

DY Not at all. It all happened very quickly. Like slipping on the stairs, when you keep going faster and faster and can’t seem to stop! We’re accidental restaurateurs.

GS As the group grew, did you feel the need to conform to what other restaurants were doing, food-wise?

DY Not really. I don’t think that’s a good thing. As a shop on the high street, you wouldn’t expect your customers to tell you what to sell and as a restaurant it’s no different. We decide on the menu, we provide our customers with a choice and we hope they enjoy our food. If they don’t then they are free to eat elsewhere.

GS But you are about so much more than the food. It’s about the experience.

DY Yes, and this is where the interior design comes in. But, like the food, we realised that you can’t design for everybody. You have to design interiors that you think are good and then hope that your customers will like them too. It’s all about a lifestyle, it’s the food, the service and the interior design. But the design is very much at the core.

Main image: Aqua Nueva, London. Top right: Shiro London. Bottom right: The Chinese Library, Hong Kong

GS When you create your interiors are you influenced by other interiors?

DY We all are. I think that if you’re a creative person then you’re always absorbing the stuff around you. So of course one is influenced by others. I don’t think that many of us are terribly original, but good design should be an evolution of ideas.

GS When you first visit a new site, can you see instantly how the space will look and work?

DY Yes, I can. In fact, I tend to take interior photos on my phone, and using a pen, I start to draw in the detail over the photo, like an archway or a chandelier, and then I get an architect in to do the proportions for me. And that’s how our interiors develop.

GS Do you apply that technique with existing buildings and with new build

DY I do. I did it with our restaurants in the Shard and I’m doing the same with an old fire station. I’m creating 3D restaurants in my head. So, when the proportions are finished, I have everything produced remotely and all of the pieces made in Hong Kong. I don’t actually see the pieces until they get here. But they’re made with such precision that we simply assemble them when they arrive. It’s like building a Lego house!

The Chinese Library, Hong Kong

GS Do you always go abroad for suppliers?

DY Well suppliers in the UK are not competitive enough. And they just can’t compete on price. So, our furniture supplies come from China, from Turkey and from Italy. And our metalworks come from Italy. With our restaurants in the US, we source our suppliers mainly from Canada. Suppliers in the US are too expensive. They’re eye-wateringly expensive!

At the moment, we’re looking at India, so we’ll probably be working there with Indian designers.

Above: Azzurra London (top left), Aqua Nuera London (bottom left).

Aqua Kyoto, Paris

GS Your first UK restaurants opened in Regent Street in central London. You took on over 17,000 square feet. Wasn’t that quite a gamble?

DY I didn’t see it that way. I’m not a gambler. I knew that site would work because of its size. We put in two restaurants and a large bar and there were extra rooms and terraces, perfect for private events. In fact, 20% of our income now comes from the private events.

GS Were there any pioneering restaurants or restaurateurs that influenced you at that time?

DY I was a great admirer of Sir Terence Conran. I loved the glamour and the grandness of his restaurants, like Guastavino’s in New York and Quaglino’s here in London.

GS Do you have a business formula to follow when you open a new restaurant?

DY Well, the formula is really about hitting the right price point.

GS And how do you know what the price point should be?

DY It takes a long time to get it right. Firstly, you need to understand that you can’t serve everybody. People have very different income levels so obviously they won’t all have the same budget. You need to know your demographics. You need to know the general age group you’re targeting, their spending power, how often they like to go out, how much they’ll be willing to spend on an evening meal, and so on. And then you need to see whether that fits. And, importantly, if it fits in that area. There are some things that work here in London for example, that wouldn’t work in Liverpool or in Manchester.

GS Would you consider opening in other UK cities?

DY We’re looking at Manchester at the moment and also in Birmingham, although I don’t know Birmingham that well. And we’re keen to look at some of the big university towns, like Oxford, for our second-tier restaurant concepts, like the Library and Shiro.

Aqua Kyoto, London

GS When you are travelling with your work, which hotels do you like to stay at?

DY I tend not to go for five-star hotels, because when I’m working, I’m always on the go. So, for me, I like nice simple, quiet hotels, with good wi-fi and a comfortable bed, and no further distractions. When I’m working, I’ll just turn up at the hotel, drop off my bags, and then go out for site visits and meetings, pretty much all day long. I spend next to no time at the hotel.

GS Didn’t you run a hotel?

DY Yes, we did. It was called Hullett House, in Hong Kong, and it was voted as one of the top 50 hotels in the world. And I designed all ten suites. It was in the former Marine Police Headquarters in Hong Kong.

GS Why did it close?

DY The landlord wasn’t very cooperative, and it had no decent access, so it was a difficult building. It was actually on a hill with escalator access from below, and that was unreliable. They’d stop it from running when it was raining. There were various other issues too, so we were glad to get out of it as soon as we could.

GS Would you open another hotel?

DY No. I did that one because of the F&B (Hullett House had five restaurants) and, because of that, I had to do the rooms. We didn’t consciously look to open a hotel.

GS Would you be keen to open your restaurants within other hotels?

DY We did a pop-up in the Shangri-La hotel in New Delhi. I’m not against the idea of more. I have been approached many times by people with suitcases full of cash trying to get us to open with them, but it’s not just about the money. Every restaurant I open is my baby! And I’m not giving them up for adoption any time soon!

You have to be very careful about the partnerships that you enter.

Shiro London

GS What has been your biggest business challenge?

DY Trying to save people’s jobs during Covid. In the UK we had furlough, but in Hong Kong we had over 550 people working for us and the government closed us down, with no compensation. Not for us, and not for the staff. It was horrendous. How did they expect people to survive?

Actually, here in the UK they did say we could stay open, but with glass partitions between every table and two metre spaces between everyone. So, that just wouldn’t work – the economics didn’t work. We couldn’t pay our rent, because we had no income. So, we struggled. We tried to stay open by doing takeaway food. That helped a little but ultimately, I decided to incur debt myself, because behind every chef working for me there was a family that needed feeding and children who needed to go to school.

GS Didn’t the restaurant industry rally and lobby the government for more practical business support?

DY When Covid came, it was panic time. The government were just looking at how they might help people in general, not specific industries. There was a big issue about landlords and rentals. The landlords wanted their rents on the basis that Covid wasn’t their fault, and restaurants weren’t prepared to pay on the basis that they couldn’t operate their businesses.

GS What advice would you offer to someone starting up in the restaurant business?

DY I would say you must follow your passion. This is not just a job; it’s a chosen lifestyle that requires passion and conviction. Without that you’re never going to be an entrepreneur.

GS What’s the plan for the future? Is there an end game?

DY There’s no cut-off point for me. I think if you start thinking about retirement or exit plans you begin to take your eye off the ball. As long as I still have my passion, and I’m still relevant to the industry, I will carry on going. And I’m very happy to do so.

GS Do you have the same level of passion that you had twenty-five years ago?

DY Without question. I love my job, and I love every aspect of what I do.

GS In terms of personal achievement, would you say that you’ve achieved all you want to achieve?

DY No I wouldn’t. There are things I want to do in terms of giving something back to the industry. When footballer Marcus Rashford was shaming Boris Johnson about providing meals to kids at school, I was genuinely taken aback. The government could do so much more, and it made me realise that there are things I can do to help. Perhaps in terms of organising and managing things. I’m good at mobilizing things and I do want to help.

Secondly, I’ve always been an animal lover. I don’t eat meat. So, for me, it’s about ethical farming, and I want the future generations to know where food and produce comes from. I want to help educate people. We shouldn’t let our kids grow up not knowing where our food comes from. It’s ridiculous. And there needn’t be that much cruelty involved in bringing food to the table. Cruel practices are just not acceptable.